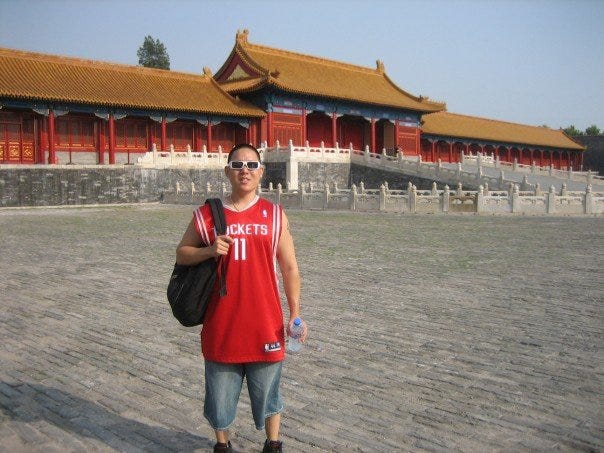

Beijing 2007

I miss hutongs

Eddie Huang is a Taiwanese-American multi-hyphenate who has made his cultural mark as an author, chef, restaurateur and director. A former attorney, he later turned to cooking and opened BaoHaus, a Taiwanese bun shop in New York City. He is widely known for his memoir Fresh Off the Boat, which was adapted into a popular ABC sitcom in 2015. Huang also hosted the Viceland show Huang’s World, which explored cultural identities through the lens of food. In 2016, he published his second book, Double Cup Love: On the Trail of Family, Food, and Broken Hearts in China. In 2024, he directed, produced and starred in the documentary Vice is Broke.

My first trip to China was in the Summer of 2007; I was 25 years old and knew enough to know that China would be changed forever after the 2008 Olympics. I knew that I would never forgive myself if I didn’t see it before the transformation because I heard old timers talk about Hong Kong before the hand-off in ‘97.

Simply put, I didn’t want to miss China.

And I didn’t.

What I didn’t know was that the best part about the China I was about to witness was that it didn’t want anything at all.

***

It was my 2L Summer in law school, but I was already checked out. I had won a NYC Minority Bar Fellowship my 1L year and secured an offer at a Top-50 firm so I cruised, as I had, through most of my academic career to that point.

Most people who secure jobs their 1L year try to get a better job their 2L year, but I didn’t care because I was told that the Top-50 firms all generally pay the same amount and I didn’t have much interest in the law besides my internship at The Innocence Project, which of course paid nothing.

At the firm, my most prized skill was the ability to play fantasy football. As a writer for Rotowire, when they were the dominant fantasy sports publication, I was able to bill hours of fantasy football research to certain “matters”.

My master plan was to make whatever I could make at the firm, until I was eventually fired for being useless besides an ability to play fantasy sports, flip it into Nike SBs, streetwear, weed, then sell it all at a profit and retire.

This is what my studio apartment at 201 E. 12th Street looked like that summer.

I was mentally fat and comfortable and satiated.

In scientific terms, I was a real ungrateful, know-it-all, piece of shit, which was an unknowing pattern because nothing was ever good enough for my parents. They demanded academic excellence and I achieved it, but I was never curious which is a really boring refrain, but sometimes what is boring is true.

In 2007, I had no concept of any of this.

I saved most of the money, but set aside about 10k for a summer in Beijing because I was curious about China.

***

My Big Aunt had an old friend who’s son, Greg, lived in Beijing and offered to be my de facto guide. Greg picked me up at the airport, took me to a fantastic Sichuanese dinner at a popular restaurant with his mother then drank Moutai late into the night before dropping me off at the dorms I would be staying at.

I had signed up for a Chinese language course intending to attend some classes, but ultimately only went to two. It was still a great deal though because enrolling in the program and staying in the dorms was significantly cheaper than going to a hotel.

Of course, when being hosted you should always bring a gift for your host. I wanted to bring Greg something decidedly American, and of the moment, so I chose Obama T-shirts since it was 2007. Before Shepard Fairey or anyone else printed Obama T-shirts, I made Chicago Bulls T-Shirt Jerseys that said OBAMA 08 on them, walking around with grocery bags full of tees, selling them to people on the train, on the street, and in boutiques like Union or King Stampede.

When I gave Greg the T-shirt, he asked me, “Do Americans like Bush?”

Greg, wanting to be polite, mentioned that his decisions were confusing and that he didn’t seem to be the best public speaker. As I traveled through Beijing that summer, this was a constant theme. Everywhere I went, every cab I got into, people asked me what I thought about George W. Bush because I was clearly American by the way I dressed, but I could also speak fluent Mandarin.

I became a lightning rod for everyone’s burning questions about America, the Asian-American perspective, and how it was possible someone who seemed so “slow” and “out of touch” could be the President of the most dominant country in the world.

Going to China that summer, I expected a lot of Chinese pride.

As a Chinese-Taiwanese person in America, I was feeling it. There was talk about China’s return to the global stage coupled with the initial rumblings of Chinese fear since every thing was already made there; people were starting to respect Chinese food; there was ample attention surrounding preparations for the ‘08 Olympics and Yao Ming was becoming a force in the NBA.

But when I went to basketball courts or, say, the Forbidden City, I was the only one wearing a Yao Ming jersey.

What I did see were Allen Iverson jerseys EVERYWHERE. On every street in Beijing at that time in 2007, most Chinese kids wanted to be Allen Iverson.

Being from DC, I was a rabid Georgetown fan and still remember where I was as an 11 year old watching Allen Iverson’s first game: at this kid, Mike Isler’s house. I didn’t miss a single televised game of AI’s college career, but when Yao came onto the scene, I flipped. I wore Yao Ming jerseys everywhere because I related to his experience immigrating to the NBA, getting shit on by people like Charles Barkley or Shaquille O’Neal (people who were my heroes growing up), and I just wanted to see him win. If I could see Yao win, then it was as if I could win in America too.

But people in China couldn’t give a fuck less!

It was as if I’d been tricked into some sense of national pride for a country I didn’t even grow up in. That all the jokes I heard and all the taunts about being Chinese had distracted me from enjoying being American, which in the minds of Chinese kids at that time was SO much better.

My childhood as an immigrant in another country made me yearn for and defend something I didn’t even understand: being Chinese.

Sure, people in politics or media probably had a lot to say because they could perhaps piggy back on Yao’s success, write op-eds or do whatever the equivalent of a Substack Newsletter was in 2007. But PEOPLE simply didn’t care because they lived in a city and country where you could mind your business, provide for your family, and have fun without any acknowledgment or interaction with the global rat race going on.

They didn’t have to compete.

They didn’t need representation or reinforcement or pride about being Chinese.

They just were.

That is until the preparations for the Olympics started to encroach on their neighborhoods.

***

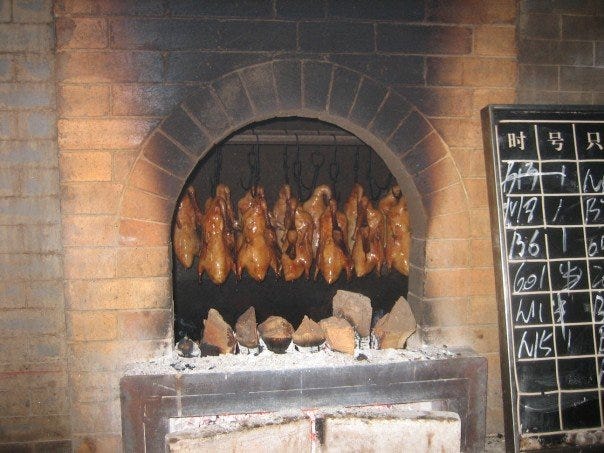

After two weeks of hitting the legendary restaurants everyone tells you to hit like Quanjude or Da Dong for peking duck, I started to hang out in Hutongs.

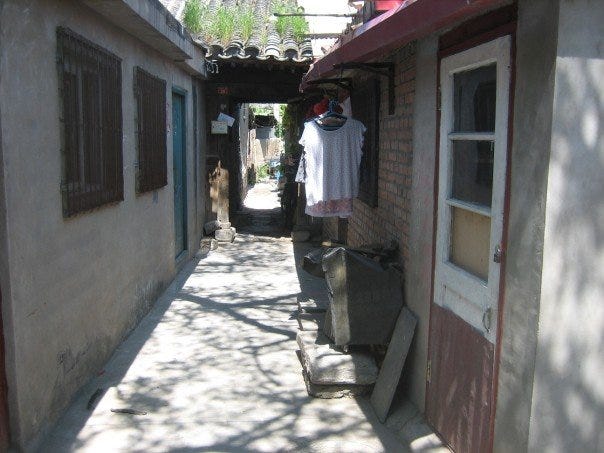

Hutongs are simply put old alleys. The word comes from the old Mongolian word for “water well” signifying the communities that would form around a water well in ancient times. There isn’t anything you would geotag in a hutong. Sure, there were a couple good noodle spots, snack spots, but really it was a place to hang out unbothered and observe “China”.

For Chinese people, it’s simply their home like how Orchard Street was simply home to Jewish immigrants or Alphabet City was simply Loisaida to Latino immigrants. In the same way I’d play ball and cop coco helado sitting on a bench in the lower, that’s what it was like in Beijing’s hutongs in 2007.

Some people may feel there’s nothing to see or do in a hutong, but to me it was everything. This was the “China” I came to see. The China that resulted from the Opium Wars, the devastation of World War 2, the decision to close its doors to the rest of the world until 1977, and landed most of the country in abject poverty.

I’d seen this version of life in hutongs from films like Shower, Beijing Bicycle, or Jia Zhangke’s masterpiece Xiao Wu about the town pick pocket.

This life was hard. What those movies depicted and I experienced observing life in the hutongs was life without any promise. They could pray, they could beg, they could work their asses off the rest of their walking days and never ascend because there simply wasn’t opportunity in the hutongs.

I didn’t know what it was yet, but I was convinced there was something to learn here.

Whenever I sat in the hutongs for an afternoon, one of the old timers would ask me, “What are you doing here? You like this?”

They didn’t understand why someone from America with money and opportunity and good health would want to be in a place like the hutongs, but after several visits a narrative started to reveal itself. My appearance started to shed a lot of its accessories: sunglasses, jewelry, hats, and eventually I started to roll my shirt up and sit with a Beijing Bikini like every one else. I went from eating Peking Duck to 5-cent noodles with barely any discernible protein washed down with Erguotou, a Sorghum based alcohol produced and distributed by government distilleries that we drank in plastic cups even though it immediately melted the edges on contact.

Of course, the therapeutic benefits of the hutong were minimal since I was projecting a lot of it.

When I wasn’t with the old timers, I got in arguments with people my age shooting dice playing drinking games. When I played basketball at the park, I didn’t respect the foul someone called and ended up in a 1v5 fist fight that spilled into the barber shop next door.

When I expressed my frustrations with life, basketball, or dice games, the general consensus from the old timers was simply to “take it easy” and look at what you have. Nothing I was frustrated about seemed worth it to them and in the same way they helped me accept my station in life, they seemed to understand the benefits to theirs as well.

But ultimately, nothing is immune to change. As the hutongs were being knocked down in the Summer of 2007, I saw photographers shooting the “New China” through the rubble of the old China. What was left of the hutongs simply framed a new portrait.

In particular, one photographer Xu Yong had work at 798, China’s first recognized and protected arts district, where I saw images like this preserving the history of the hutongs.

By the summer of 2008, China awoke from its slumber and arrived on the global chess board in an axis shifting way. When the olympics began, most of the hutongs had been destroyed. A few are now preserved as cultural landmarks with rows of street vendors installed for the enjoyment of tourists and it looks like this.

China is a super power and I can’t fault Xi Jin Ping or The Chinese Dream. This generation of children born in Beijing are starting from a place with promise. They have a chance, they have mobility, and with that comes self-determination.

While the people in hutongs helped me “take it easy”, that’s not their function. They aren’t old wisemen to keep in hutongs like Shamu at Sea World waiting to dole out advice. By joining the rat race and taking their place on the world stage, China gave its people choice.

But as we understand in America, choice can be a very dangerous thing that requires immense self-control when tethered to a world that moves and changes by the millisecond. I don’t even think it is possible to exercise the level of reflection and self-control necessary when our actions are visibly projected to the ends of the Earth with incredible force and speed without any visibility of the cost.

All of us are constantly shouting and posting into the void surprised to receive backlash or negative commentary, but it should actually be expected. How could any of us have the foresight or understanding to know how someone is feeling in another city, time zone, or country with any real certainty when I could barely understand the thoughts and feelings of people I sat with in the hutongs for hours on end.

When we visit a place for a few days, we think we saw it. We hit the top 5 restaurants, take the photo, post the video, write the newsletter, but all of those things are self-justifications. They are actions deflecting the very real possibility that we don’t know shit in an effort to preserve self-image on the internet. After spending all this money to travel, the last thing you want to feel is that you lost the plot or missed a spot or did it wrong.

I stayed in Beijing for 2 months.

I missed pretty much everything you are supposed to do besides eat Peking Duck, but it was one of the most important trips of my life sitting in hutongs on a stool with a Beijing Bikini on, getting a glimpse of China before it was gone.

So much of this rings true to me as the child of first gen immigrants from Finland after WW2. I moved back there in 2000 (also in my early 20s and from DC) with sooo much Finnish pride and misplaced ideas and had a very similar reception and questions from everyone I met about why we elected W. Woof. Embarrassing.

I was born in Taipei, raised in the States, with Waishengren parents -- this was a very relatable read. My parents wanted me to experience China back in ~2006/2005. We made a trip to Beijing, Xi'an, Shanghai....I was about 14 years old then, too young to understand what was happening at large and what was to come. I wish I was a bit older to recognize how special that time was.

"My childhood as an immigrant in another country made me yearn for and defend something I didn’t even understand: being Chinese."

Thanks for writing that.