Japan: Part 1

The first of a three-part series exploring family, history, and travel in my return to Japan.

Sean Thor Conroe is a Japanese-American writer born in Tokyo in 1991. His debut novel Fuccboi was published by Little, Brown in 2022. He has guest edited New York Tyrant Magazine and hosts the book podcast 1storypod.

Thursday, April 24 — 10 PM

At an Airbnb just south of the Tokyo Skytree. Three weeks today since I’ve been back motherlanded. Checked into this spot yesterday, Amelia arrived on a red eye from Bali early this morning. She’s behind me working on her iPad, on the bed—there’s no couch.

I’ll admit, the spot felt a bit small, smaller than advertised, when I first saw it, and I was initially worried Amelia wouldn’t like it. But it’s clean and quaint and quaintly understated, minimalist yet thoughtfully laid out. She likes it.

And what a relief that was, it’s something of a miracle that she’s out here, that we’re both out here, together, in Japan, with no return flight and a clean quaint Airbnb—that she likes—just south of the Tokyo Skytree for a week. It’s essential, in circumstances like these, traveling together, to keep her happy. And that starts with our home.

It’s in a neighborhood I’m completely unfamiliar with, Sumida City, across the Sumida River from Central Tokyo, but not all the way out across the Arakawa, which marks the boundary into Edogawa City, where I was born and spent my first three years, in Kasai. Where my baba lived till she passed away last month, five days before her 95th birthday; where my uncle Nobu still lives; and where I stayed the last two nights, in my baba’s old room, after flying back down from Hokkaido, where I spent ten days with my dad, just my second time seeing him out here since he expatted 12 years ago.

*

A week before my baba died, she fell. She cut her leg and then it didn’t heal right.

When my mom called to tell me this, I was posted in a yurt with a wood burning stove, upstate at my cousin’s, squatting on my cousin’s property. I’d been back itinerant, subletting out my NYC apartment and roaming, since the New Year. Waiting on TV option money that was taking forever to come through.

When my mom called me a week later, telling me my baba had passed, it was a week before spring. I was in Harlem, I’d been crashing at my boy Al’s empty apartment—he’d moved out, but had it rented still thru the month—sleeping in my sleeping bag on the floor, staying over at Amelia’s whenever she was feeling benevolent enough to let me.

I’d already been wanting to exile in Japan, to see my baba for her birthday, and to ask her all the questions I’d been meaning to ask her, when I learned this.

I booked my ticket out, for her funeral, that week.

Ten Years

All month, I’d been going around saying it musta been “7 or 8” years since I’d last been back (in retrospect, subconsciously estimating “around 7” for the Biblical, Homeric resonances—Jacob waiting for Rachel, Odysseus stuck with Circe), but it had in fact been ten years exactly. Since April 2015, when I was 24.

And it had been ten years exactly before that, in 2005, when I was 14, that I’d been back before that—for my gigi’s funeral.

My little sister, my mom, and I went on that trip two decades ago, I remember the funeral well, my sister’s a year younger than me so she was 13. And then on that trip a decade ago, in 2015, when I was 24 and my sister was 23, I stayed with her in her apartment in Nakameguro, where she’d been living for two years, doing modeling and au pairing. She showed me around that week, helping me navigate, speaking the Japanese she’d worked on for two years and grown proficient at again.

Now I was 34, and my little sister was 33, with two kids. I flew out to hers first, in LA, and my mom joined a couple days later so we could all fly out together, my mom, my sister, the two babies—a three-year-old boy and two-year-old girl—and me.

What’s wild is, those were the ages my sister and I were when we first left Japan, in the spring of 1994—almost ten years exactly before that last time I came out here two decades ago, I’m on a strange decade-increment schedule of trips back home to Japan.

Flying Out

We were gonna all pile into my baba’s, but my uncle Nobu got us an Airbnb instead, about a mile east of the Kasai station. On a small river, the Shinkawa, kawa means river. We flew out on April 3, the funeral was April 5—not the 4th since fours are bad luck. The week the cherry blossoms bloomed. The river our bnb was on was lined with cherry blossom trees.

Flying out 12 hours with two babies was something different. The same flight the other way basically that we did when we were their age, the other direction. At one point, about eight hours into the flight, little Toto, the two year old girl, looked out the window, and in a moment of evolving spatial awareness, got totally terrified and scrambled aisle-ward, onto my mom, and had to be calmed down. I’m the fun uncle but on this trip I’m expected to be the stand-in dad. Selah is getting used to not being the only baby, and Toto is so damn cute, if Selah notices how enamored by Toto everyone is, he’ll do something completely menacing, break something, to make everyone look at him. Or worse, do something mean to Toto. My sister keeps joking that they’re exactly like how we used to be. Also like us, everyone will turn on Selah for being a menace, except for Toto. She loves him and copies everything he does—Selah will spit on something to divert attention away from cute Toto, and then when I get mad and tell him to stop, Toto will laugh and start spitting too, to make me tell her to stop, only she’s too little so will just make a weird shape and sound with her mouth, laughing and checking how Selah does it, to most accurately emulate him.

We’re completely beat when we finally make it off the hourlong bus to Kasai, after 24 hours of traveling. It’s night again. My mom heads to baba’s, she’s got prefuneral duties, whereas my sister and me and the babies walk to the bnb. It’s a straight shot on the main east-west thoroughfare. I keep walking on the right side. I forgot how many bikers Tokyo has. My dad will be joining us the next day. Too tired to go to a real restaurant, we take the babies to 7-Eleven and go crazy on their premade food—soba, stir fry, onigiri, sushi, a yogurt drink, a huge bag of chocolate croissants Selah grabs.

The First Morning

The first morning, we walk over to the playground right by my baba’s apartment. Selah and Toto play right where we used to play. On the swings and the slide. Then we meet my mom by the Kasai station and go a couple stops over to Monzen Nakacho, where my mama grew up. We walk down along the river and see the cherry blossoms, and then on the way to this lunch spot, stop by her old kindergarten. It’s no longer there but there’s a new one, a playground with a bunch of small children playing. They all have matching green hats on. One very talkative girl kept wanting to talk to Selah, he must’ve looked very exotic to her with his long locks and multi-ethnicity makeup.

Selah got all shy.

When we left the little girl started making a crying face and looking down despondently.

In order to get to the lunch spot my mom wants to go to, we walk through the shrine attached to my mom’s old elementary school, across from the temple—this is a thing, a shrine next to a temple, my mom explains. I almost walk through the archway into the shrine but my mama stops me—if someone close to you dies, you don’t walk through the arch, you walk around it. It’s bad luck and if you do, someone else close could die…

Back at the Airbnb I nap and then go pick up my dad from the bus station. It’s the first time he and my mom have seen each other in years. We sit on the river while the babies nap. We eat Thai food that night. The funeral is in the morning.

The Funeral

Funerals in Japan are much different than in the west. They’re open casket, there’s a Buddhist priest who does a service that includes chanting, drum beating, a delivery that ranges from muttering to droning to almost singing. There are gongs. And hand motions that are based in prayer hands, but that deviate from them, fingers intertwining, splaying, in a series of configurations that look at times like gang signs, at others like spell casting. The service is followed by attendees surrounding the open casket and filling it with flowers, first around the deceased’s legs and gradually up to her face. Close family members will place objects onto the deceased to help her pass peacefully into the spirit realm. My mama put crayon drawings my sisters and I drew on a trip we took with my gigi and baba when we were little, along with Ukranian eggs my mama made, that my baba had held onto and kept on her wall. After her casket is filled, the men carry it into the hearse, it’s transported to the crematorium, we do one more service before it is entered into the oven, and we eat a meal and drink until her body is cremated, setting aside a place at the head of the table, and a plate of food we don’t touch, for my baba.

Then we go together down to where the body is, it’s been reduced to bones, and stand on either side and transfer the bones into an urn—starting with the feet, moving gradually up to the skull, picking up the bones two at a time, a move that is taboo in any other context, two people touching the same thing with two different sets of chopsticks, it’s done only for cremated bones, to help each other carry the load of grief, and also to give baba extra support as she passes over. The last thing that’s placed into the urn is the hyoid bone, since it supports speaking and eating and swallowing. The coroner lifts it up and shows it to us, maybe twelve of us, the funeral initially consisting mostly of my uncle Nobu’s work clients, this later more intimate group is just my mom, my sister, her babies, my dad, my mama’s best friend Ma-chan, and three of baba’s cousins, one on her side and two on my gigi’s. He does this somberly yet somewhat coldly I feel, displaying it almost like it’s an art object. I had about three beers and some sake during the cremation meal, a bit more than I meant to, and something about seeing baba’s hyoid bone displayed like this gets me lightheaded and slightly nauseous, it’s almost like an auctioneer how the coroner is holding it, speaking in a calm, even tone, in his suit and his white gloves, the bones are still smoking slightly, they’re much lighter and more fragile than you expect when you pick them up, there’s a crustaceous quality to them, even a botanical aspect to the hyoid bone specifically, symmetrical and ornamented florally. Like sea creatures, I think.

But no one seems visibly shaken.

Kire, ne, baba’s cousins murmur. Beautiful, huh—leaning forward to have a closer look.

There’s a six-inch metal rod with screws on it that juts out abrasively partway up the casket—from my baba’s hip, from the first of her three falls, my mama estimates. The coroner starts to pick it up and move it towards the urn, but Nobu goes, Iranai—we don’t need that.

Baba’s hip bones and skull look like big white shells. Though we notice a vague rainbow tint to some of them, some streaks—purples and pinks.

The coroner looks at them mystified as he transfers them. We all lean closer.

Why are her bones like that?

Till finally my mom realizes.

Our drawings. My mama’s Ukrainian eggs. Turned baba’s bones colorful.

As the first (and for that matter last) born grandson, I get tasked with carrying the urn home.

My dad had been calm the whole service, but he’s having a bit of a meltdown on the bus from the crematorium back to Kasai. I’m hugging the urn to my lap. My dad’s been on a longevity kick, he’s been lifting weights, he quit smoking and drinking, he Zyns nonstop.

You alright there, pops.

I mean, he says, sweating. I’m almost seventy, man. My time has almost come.

———

Thursday, April 24 — 11 PM

Just after 11 now. Back at my desk. We’ve both been up for so long, we should be crashed out, but we’re too excited to sleep. Amelia wanted to walk to the 7-Eleven and back. We almost got the strawberry whipped cream sandwich, but decided to hold off till lunch tomorrow. Amelia just so happened to be traveling out to Bali, for a twenty-day yoga teacher training, right when I ended up coming out to Japan. We’ve been in the same time zone, just one hour off, all month. Her training ended last week, right around the one-year anniversary of us meeting. Neither of us were wanting to go back to New York, so she decided to get a ticket out to meet me on a whim.

There’s an aspect of colliding worlds to Amelia’s arrival out here, of someone from the states coming to see me in this environment, I was so nervous for her to arrive, I barely slept last night. And it was so surreal when I found her curled up against a pillar, waiting for me, in international arrivals this morning. We took the train back through the rice fields in the outskirts, past the especially green-seeming trees, and started walking south from the Skytree station. Amelia was on no sleep either, looking around at everything so unfamiliar. I asked if she was hungry, she wasn’t hungry, what about anything to drink, she said no just water. I dropped her off at the spot, got her set up, showed her the shower, the heated toilet seat, the back and front temperature and pressure controlled bidet, and headed to the conbini. I got two onigiri, a tonkatsu sandwich, two iced coffees and a big water. I came back to find her dozing off. I put her dirty clothes along with mine into the wash and then took them down to the laundromat to dry them, and once she got up she was suddenly energized and hyper and excited, she couldn’t believe she was out here, I couldn’t either, I still can’t, she ate an onigiri and we headed off along to the canal and ended up at the Sumida River park on the Sumida River.

Shinto vs. Buddhism

When I wrote about my gigi’s funeral in my novel, I said it was a Shinto ceremony. This wasn’t totally correct.

Ten days ago, walking down to Shiosai, the town hot spring in the oceanside fishing town where my dad lives, past the scallop boats cleaning the scallops they caught the night before—they fish between 2am and 8am each night, Indonesian and Vietnamese immigrants on temporary work visas mostly, through some Japanese as well—walking through the pungent fish smell, I bring this up.

Wondering whether the Shinto burial, with the bone ritual, is specific to Japan.

Well no, the funeral wasn’t Shinto, my dad says. It was Buddhist.

Shinto, it turns out, is different from Buddhism, it’s indigenous to Japan and predates Buddhism’s arrival in Japan from China. It’s characterized by the worship of one’s ancestors, and the belief in kami, or spirit, the all pervading god-spirit, that flows through all objects, both animate and inanimate. There is no dogma in Shintoism, its festivals are seasonal celebrations of birth and life. Buddhism, on the other hand, concerns death—weddings, for example, are Shinto, whereas funerals are Buddhist. Likewise shrines—identifiable by the rectangular archway, the torii, at its entrance—concern birth and life, whereas temples, which often have tombstones, concern death.

The fishing town my dad lives in, on the coast of the Uchiura bay, near Lake Toya, slopes up steeply from the ocean, and is overlooked by the town Temple, my dad clarifies.

“But what about the picking of the bones? Is that Buddhist?”

My dad isn’t sure.

Yesterday morning, before taking the bus over to the Sumida City bnb from Kasai, to check in in advance of Amelia’s arrival, I get all packed up and then sit on the couch with my mom and ask her questions for this essay. Check in isn’t till 4. A lot of this stuff was just how she was raised, and she doesn’t know the technical answers. We both research.

This specific process of cremation, we learn, is specific to Japan. Cremation initially was reserved for the wealthy, and the proliferation of it into the general public had largely to do with the practical matter of space: Japan has over one-third the population of the United States, and yet is about the size of California; what’s more, only three-tenths of Japan’s square-area is inhabitable by humans, the rest being mountains or other uninhabitable terrain. Point being, cremation allowed for families to take the urn of the deceased home and add it to their altar, without taking up limited real estate. It’s the first thing you do when you enter my baba’s home: go to gigi’s altar and light a stick of incense and blow it out and plant it into the bowl of ashes and strike the gong and put your hands together and commune with gigi.

Shortly after returning the urn to my baba’s, members of the funeral home came by to help put the altar together in the proper way. Along with flowers, a photo of baba, and the incense setup, we put some snacks that baba liked in a little bowl for her.

Birth vs. Death

For the final step of the funeral process, we were given these special salt packets and instructed to throw salt onto ourselves, to rid ourselves of death, right before entering our homes and returning to the world of the living. As unsentimental about death as the funeral process was, from the immediate contact with the open casket, to the direct handling of the bones, death is something that has its time and place and must be kept away in the world of the living. This is the same with evil in Shinto: it’s not something that banishes certain individuals to hell eternally, but rather something caused by evil spirits that must be kept away with rituals. Shoes, for example, are only worn indoors in one context, to carry the coffin out; it’s for this reason that removing one’s shoes indoors is practiced so rigorously in Japan—it’s to keep death away.

The week before I left, I was hitting all these anniversaries of deaths that happened the first week of spring four springs ago, staying in Al’s Harlem apartment, in the same neighborhood I lived in when they happened. I was the editor of a literary magazine at the time, but it would be ending due to the deaths, and for the last piece, I published a birth diary my mom wrote, with a picture of my baba holding my mom when she was a baby. And now my baba had passed, a week before her birthday. I like this idea of confronting death fully when it arrives, but to separate it from the world of the living once you return—to look at birth and life as in a separate domain than death, with separate practices, even separate houses of worship.

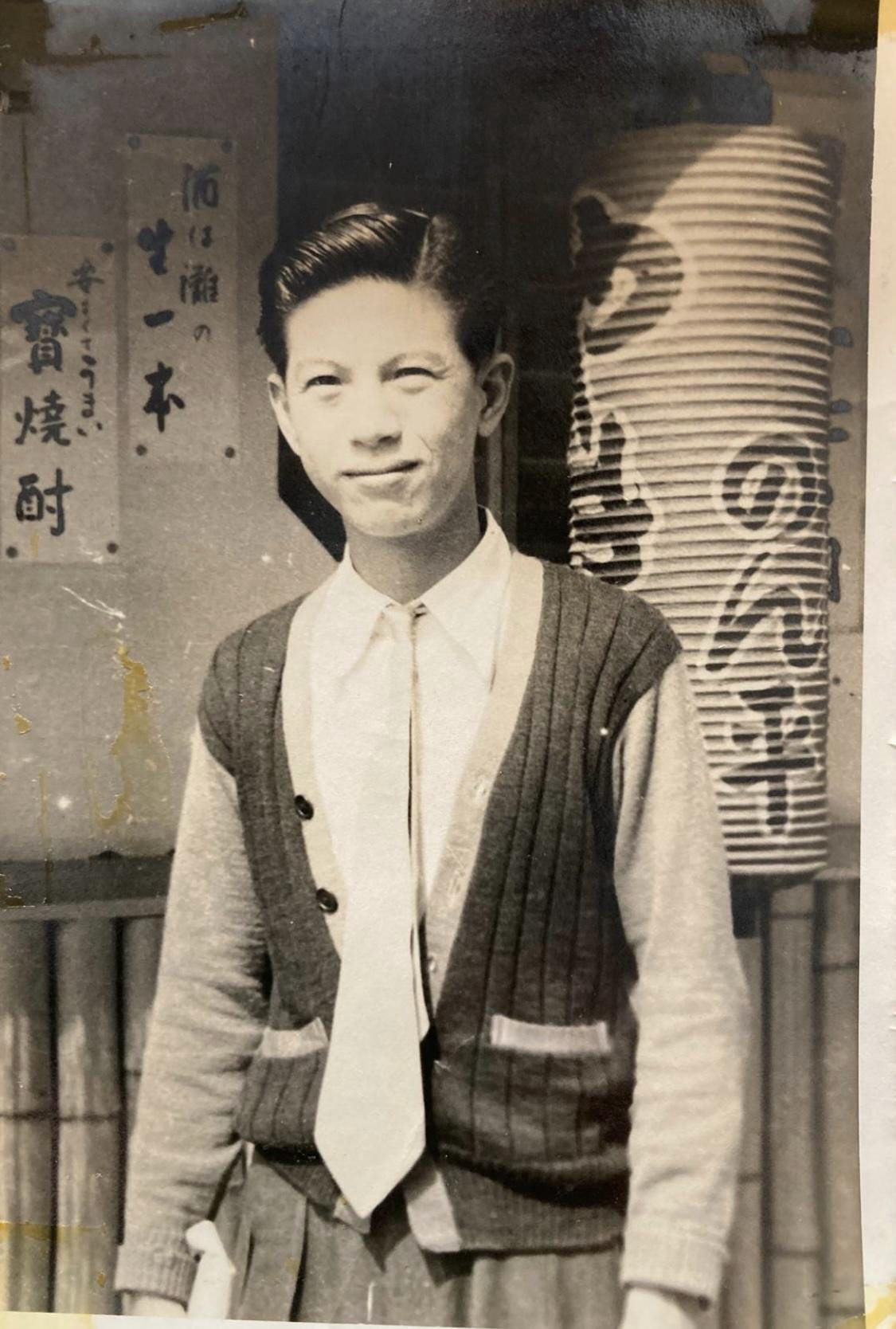

My baba was born Saito Masako in 1930, a couple hours inland from the sea in Ibaraki, the prefecture north of Tokyo. Her mother died in childbirth. She studied garment making, both western and Japanese styles, so dresses and suits but also kimonos, and moved to Tokyo to work at Marui, a department store, as a seamstress, in her early twenties. At age 25, she married my gigi on arrangement by a mutual acquaintance, and in 9 months almost to the day gave birth to my mama. This was in 1955. My gigi, Etsuo Kamura, worked as a clerk for one of Japan’s five major newspapers, Yomiuri—of Yomiuri Giants notoriety, they’re the company baseball team.

Once, when my older sister visited my baba, my baba showed her boxes and boxes of diaries she’d written. My sister said they were how she would deal with having to take care of gigi full time in his final years. Whenever she’d feel overwhelmed or trapped she’d write and write, to transport herself elsewhere, to vent. I asked my mom about them yesterday, she hasn’t been able to find them, though there are a couple closets of papers she’s still sorting through. They’ve gotta be around somewhere. My mom said it was hard for my baba, having first to take care of gigi’s dad, who lost his wife and two children—gigi’s siblings—in the Tokyo fire bombings, and was already approaching old age when she and gigi married. Baba took care of him. And then that process got repeated when gigi grew old. My baba was not only totally independent until months before her death, but took care of others, right up until she died. She walked every day, all 4 foot 5 of her, to the market and back. I don’t want to be a burden on anyone, I want to be not only independent but able to care for others like baba.

Checking In

My mom was worried I wouldn’t be able to check into the Airbnb by myself yesterday, the email was entirely in Japanese.

I tell her I should be all good, I Google translated it.

Still, she says, better to be sure. She doesn’t have anything on her agenda for the day anyway.

On the bus ride over, we pass my mama’s old high school, Komatsugawa. She’d take a train over and then a trolley, the trolley no longer runs but the high school is still there. It’s a cloudy day, it rains on and off. I google things in the area I’ll be staying, to learn more about it. My mama tells me it’s where Hokusai was from, the woodblock artist who made the wave that is the wave emoji on our iPhones today.

It ends up being a bit of a shit show when we get to the Airbnb, we get let into the vestibule area, but then can’t get into the building proper or back out somehow, and only manage to after a frantic email exchange with the Airbnb hosts.

Once checked in, my mama and I walk a mile straight north—we already walked a mile from the south, from the bus stop—to the Oshiage subway stop, to check where I’ll take the rapid train out to pick Amelia up at the airport first thing.

Maybe I am just like gigi, needing constant maternal care; or maybe the caretaker gene has been passed down pre-consciously to my mom.

Going Out / Tenjin Shrine

We find this tiny, excellent tonkatsu spot. It’s fun going out to eat with my mom, we can go to any hole in the wall place and she can navigate any elaborate izakaya menu, I always end up eating things I’ve never tried before. There are no foreigners at the tonkatsu spot.

After our tonkatsu, with a handle on how I’ll get Amelia from the airport, and a sense of the area straight north and south of my spot—plenty of familiarity to show Amelia around—I see my mama off for the night. I have a bunch of areas I feel confident I can take Amelia.

But then this afternoon, once Amelia got up from her nap, we on a whim walked straight west, to this canal I saw running along a park, up to where it met the Yokkojika river.

And then this evening, I started leading her south, along the route I’d walked with my mom, thinking I’d take her to one of the restaurants we’d passed, with the pictures of the bento boxes out front, that I could point to and say a little Japanese to order, but Amelia goes how about we walk this way, and next thing we’re walking due east, a random direction, towards a different river, we’re crossing the river, forging into an entirely new area together…

For the first decade after leaving Japan, my gigi and baba would come out and visit us wherever we were living once a year, generally summers but not always. They’d come stocked with two suitcases, one for their stuff, one with snacks and omiyage for us, and we’d take a trip somewhere or they’d just stay with us. This maintained our Japanese somewhat, my sisters and I.

Though of course they, both my sisters, spent multiple years living in Japan in their adulthood. I was the only one who hadn’t. And last time I came out, ten years ago, it was entirely within the guidance of my little sister, I never had to order anything or ask for directions or pay a bill myself.

Tonight was my first real test.

But so Amelia and I are walking east, towards the river, we cross the river, eye out for a good restaurant, I’m trying to be decisive and lead but everything is new and immediate and in your face for her, she’s not looking down at the map for how many stars places have, how likely they’ll have an English menu, she’s just moving intuitively, I’m following Amelia, Amelia cuts down a side alley, we cut down another lane and come upon a shrine, it’s the Kameido Tenjin Shrine, we walk through the archway, there are purple wisteria flowers in full bloom dangling over water, there are little lit up paths along them, people with selfie sticks and cameras out, we take some photos.

And after that we come upon a soba spot, I come in hot demonstrating my language proficiency, bowing and acting deferent, saying short phrases with confidence and fluency, only once we sit I cave and see if they have an English menu, Sumimasen, eigo no menu arimaska, they do, and give me one, though not without an air of disappointment, I sense, from the waiter, an older patient man with a gentle countenance, I order the cold soba with tempura for myself, the wagyu beef hot soba with a raw egg cracked on top for Amelia, then after I’m not sure if you’re allowed to order okawari (seconds) on the soba, it was kind of a small pile of soba, and I’ve killed the tempura and still have soba soup left, I see a sign with an image of soba and different prices, 400 yen, 600 yen, I wonder if these are the extra-soba-for-the-soup-you-haven’t-finished prices, but I don’t want to ask and confuse the waiter, or do something I’m not supposed to, or accidentally order a whole new order, Amelia is amused if slightly irked at my indecision, I don’t want to be a burden, I want to show her a good time and act decisively and not burden her with my indecision, I order a bowl of rice and then I pay and we hit the conbini for some snacks, this is my wheelhouse, trying every snack they have at the combini, we get an azuki bean thing and some kooky cheesecake and some cans, and now we’re back at the bnb, Amelia is in the bed behind me on her iPad, it’s been a long day, we did a lot of walking today, I figure we’ll head out and explore Shibuya tomorrow.

A slow pour. I really liked this. Thanks for sharing such a deeply personal experience.

I particularly enjoyed how you wove in the death of your baba with your burgeoning new life with Amelia and grounded it in a place that is both familiar and foreign to you. The religion tie in was a cherry on top and I appreciate the education there!

Looking forward to the next part.

This was a great read. I appreciate your pacing—it feels intuitive, like we experience the day and the thoughts/feelings with you. Your writing feels accessible and attentive to important, everyday experiences that regular people have. I want to read more work like this. Thank you